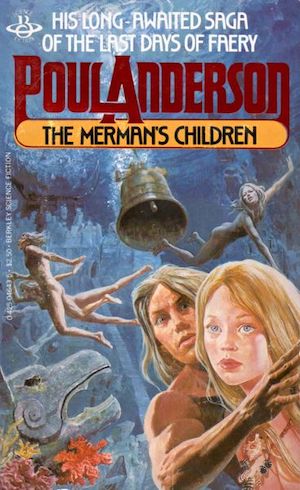

I first read the component parts of this novel when it was new, or nearly so, in sections, in Lin Carter’s Flashing Swords Anthologies. I still own the paperback of the collected stories, which were published as a novel in 1979.

Poul Anderson was one of my favorites then, for both science fiction and fantasy. He was impressively prolific and could pretty much do it all, from space opera to swords and sorcery, and he was a solid hand at historical fantasy, too. His novella, “The Queen of Air and Darkness,” showed me how fantasy and science fiction could combine into a seamless and lyrical whole. I loved The Broken Sword and The High Crusade and Fire Time.

The Merman’s Children wasn’t one of my great favorites, but some of it came back to me as I reread it. Supposedly it’s based on a Danish ballad, Agnete and the Merman, and not on the Hans Christian Andersen fairy tale. And yet it’s interesting to see how they seem to set up a dialogue on the one theme that persistently gets dropped from adaptations of Andersen: the question of merfolk and immortal souls.

Anderson’s merfolk live in a historically grounded Middle Ages, around the thirteenth century, and their world is the world as it was (or as Anderson understood it to be) at that time. They’re not the fish-tailed creatures we tend to think of as mermaids. They have legs and feet, though the feet are webbed. They can freely breed with humans, and often do; the offspring may not look quite as fey as their mer-kin, and may not have the webbed feet, but they can live underwater and apparently they share the merfolk’s physical but not spiritual immortality.

Souls are the dividing line between merfolk—and Faery folk in general—and humankind. The people of Faerie are immortal in the body, but if they die, they have no afterlife. This life is all they have. Humans, conversely, live short lives and die, but their souls live on into eternity.

Anderson’s novel explores the border between human and Faerie. It begins with the union of a human woman, Agnete, and Vanimen, the King of Liri under sea. Agnete bears her lover seven children, but she knows she can never truly be at home among the merfolk. Eventually the chiming of church bells calls her back to human life, for a short and unhappy time before she dies.

This is not a fortunate outcome for Liri, because it attracts the attention of the Christian Church, and particularly that of a pious cleric. He, outraged by the presence of soulless heathens off the coast of Denmark, pronounces an exorcism over the underwater city. The merfolk, being of Faerie, cannot resist the power of the Christian curse. Their city falls and its people are driven out.

Of Agnete’s seven children, four have survived into adolescence. Three are predominantly merfolk for looks and strength. The youngest is most like her mother; she’s fragile and weak and can’t survive the life of an exile.

While Vanimen leads the remnants of his people in search of a place where they can live safely, Vanimen’s children set out to find a home and safety for the youngest child, Yria. They place her with a kindly priest, but he insists that she be christened, so that she can live among Christian people.

Christening strips her of her memory, She becomes a new person, the human Margrete. She is very pious and very timid and very much afraid of her wild, fey siblings.

They know they’ve lost her, but they want to be sure she isn’t trapped in the convent to which she’s sent. She can stay if that’s what she wants, but they go questing for the means to keep her in comfort wherever she chooses. That means a voyage to a vastly wealthy kingdom destroyed long ago by a Kraken.

The Kraken is still alive, and fallen Averorn is still full of gold and jewels. Siblings Tauno and Eyjan and Kennin hire a wretched hulk of a ship and its equally wretched human crew and set out on a hunt for the treasure. They want none of it for themselves, only for their sister.

Vanimen, meanwhile, acquires his own ship, by theft rather than by promising a share in a treasure hoard, and tries to set off westward in search of lands that are still free for magical folk. A terrible storm nearly destroys the ship and forces it back eastward instead, into the Mediterranean and finally to the shores of Dalmatia. People there are Christian, there’s no escaping that, but they seem to be more accepting of the magical world than the humans of Scandinavia.

Both epic quests eventually converge. One of the merman’s children dies early; the rest survive, but none of them is unchanged. Nor is the merman himself, or any of his people.

Christianity in this world, with its unbending dogma and relentless conviction that it and only it is the right way to be, leaves no room for any other belief or way of life. Baptism in Christian doctrine is a process of erasing original sin—the sin of Adam in disobeying the command not to eat the fruit of the forbidden tree—but merfolk are no relation to Adam. For them, instead, it becomes a sort of spell to conjure an immortal soul in a being who has none. It wipes out the original personality and replaces it with a devout Christian.

The kindly priest who takes in the people of Liri finds a way to revise the spell. The memory of the previous life remains, but the personality alters. The person who walks away from the baptismal font is a pious Christian who can recall, if dimly, being a creature of Faerie.

There’s quite a bit of irony here, in that Christian doctrine depicts humans before the Fall as near-perfect, sublimely happy beings who know neither death nor shame. Anderson’s merfolk are exactly this. They’re not bound by human (or medieval) gender roles. Their sex lives are completely free; they don’t marry or give in marriage, they don’t have taboos against nudity or incest, they don’t suffer from body shame. When they die, they cease to exist, but they can live in the body forever, as long as they’re not killed or baptized.

Their world, at least as far as the people of Liri know it, is rapidly shrinking, constrained on all sides by Christianity. Part of the quest is to escape that, but fate and earthly weather persist in driving them deeper in rather than helping them find a way out. Nor is it only the merfolk who are feeling the pinch.

Some species of Faerie folk are even more endangered than merfolk. One of the novellas that makes up the novel stars none other than the Great Selkie of Sule Skerry. He appears to be last of his kind; he grew up alone and he sails the northern seas, awaiting the fate his prescience tells him is coming. Magic is going out of the world, he says; eventually there will be none left.

Meanwhile he proves a good friend to the merman’s children and their human allies. In human form he’s not the lissome creature we’ve seen in selkie films; he’s huge, hairy, and strikingly ugly. And yet he’s a gentle and generous person—I almost said soul, but like the rest of the folk of Faerie, he has none.

Buy the Book

A Season of Monstrous Conceptions

There’s a message in that. Is a soul really worth having, if it doesn’t make a person authentically good? Sure it gives you eternity, but what if that’s eternity in Hell?

There’s a question for another of the magical creatures the merfolk meet, the Vilja of Dalmatia. She’s also known in that general part of the world as a Wili, the ghost of a maiden who drowned herself for love. She knows she’s damned, but there’s nothing to be done about it, except to ban her from trying to seduce Christians into watery graves.

For her there may be an alternative, but it’s a sort of unlife-hack, thanks to a piece of magic from another culture altogether. The merman’s children come across a monster in Greenland, a tupilak: a creature stitched together from the parts of dead animals plus human bones, animated by magic and sent to destroy the shaman’s enemies. After the merfolk have dealt with the tupilak, they make peace with the Inuit shaman who created it, and he gives them a talisman that allows them to understand and speak all languages. It also has the power to capture a soul, which will play a crucial role in the Vilja’s fate.

Anderson’s novel is set in a time in which magic is fading or being driven out. Humans are taking over; their religion is toxic to the people of Faerie. The only way to survive, for most, is to join them. There may be hope elsewhere, and that’s where one set of characters goes at the end, but there’s no way they can be sure. The rest surrender to what they see as inevitable: death of the body but, they can hope, eternal life of the soul.

I was repelled by what happened to the merfolk who were baptized. What a horrible thing to do to them: to crush the spirit out of them, to burden them with shame and guilt and fear, to rob them of their freedom and their happiness. I cheered on the ones who resisted the compulsion to submit; and especially my favorite of all the characters, the one human woman who never lets anyone or anything get her down.

She makes a great sacrifice, from the Christian perspective. Technically it damns her forever, but what a way to go. I can’t help but think, for what she does and how and why, if the Christian God is really as merciful as his followers insist, that in the end she can have her earthly life and love, and her eternal life, too.

Judith Tarr is a lifelong horse person. She supports her habit by writing works of fantasy and science fiction as well as historical novels, many of which have been published as ebooks. She’s written a primer for writers who want to write about horses: Writing Horses: The Fine Art of Getting It Right. She lives near Tucson, Arizona with a herd of Lipizzans, a clowder of cats, and a blue-eyed dog.

“Sure it gives you eternity, but what if that’s eternity in Hell?”

All eternities would be hell. You can’t become god. So at some point you have learned everything, and done everything, and at that point eternity becoomes an endless prison. And if eternity is some overly blissful soma because of your proximity to a very flawed deity, then I would still choose no after life versus an eternity of serotonin and dopamine flooding my being. Hell would be hell, heaven would be hell. Hope for the rational, that this is the only life and this precious time we have is the only time we get to/have to exist.

This article is beautiful and reminds me of the Russian- inspired The Bear and the Nightingale. There too, early Christianity tries to drive out all other spirits or beliefs, and they do not go kindly into the good night.

Interestingly, I believe H. C. Andersen also tried an adaptation of Agnete and the Merman before getting to The Little Mermaid.

I feel like Poul Anderson must have read “Undine” (the literary predecessor to TLM) – it also has that idea of the water spirit’s personality drastically changing upon acquisition of a soul, which remains deeply unsettling. Andersen defies this plot point and goes in his own direction; Anderson explores it and fleshes it out in disquieting detail.

OR maybe when we die we’re transformed into a being who can handle & understand & be eternal.

And experience perfection which people can imagine despite our always unperfect world everyone lives in & experiences.

@@@@@ Chad Perkins: Your idea of eternity sounds shallow to me, since it’s still confined by space & time.

Humans appear to have always been able to imagine eternity & often joyously. For those whose lives are hell on earth, a life of eternity with laughter & joy & endless adventures sounds a just reward.

If there is no such thing as eternity, so much of life, & maybe all life would be tragedy, because there is always something lacking, left unfinished, unexplored, unwrote, not made, not fixed, in every life.

In eternity all things can be renewed into what they are meant to be, all wounds mended, & no weariness of time to drag people down.

I highly suggest Phantasies by George MacDonald to give a clearer understanding of what I’m trying to say.

Your last two paragraphs perfectly encapsulate my reaction to this book. I love it deeply and reread it recently, but for me it is a tragedy.